Constantly in the headlines in 2006 and 2007, blue algae are no longer part of the news. However, they’re always present and pose a real risk to human health and the environment – especially when they take over lakes.

A tool that has a lot of media exposure these days could help municipalities prevent the proliferation and risks associated with algae: the drone or UAV.

First of all, what are cyanobacteria?

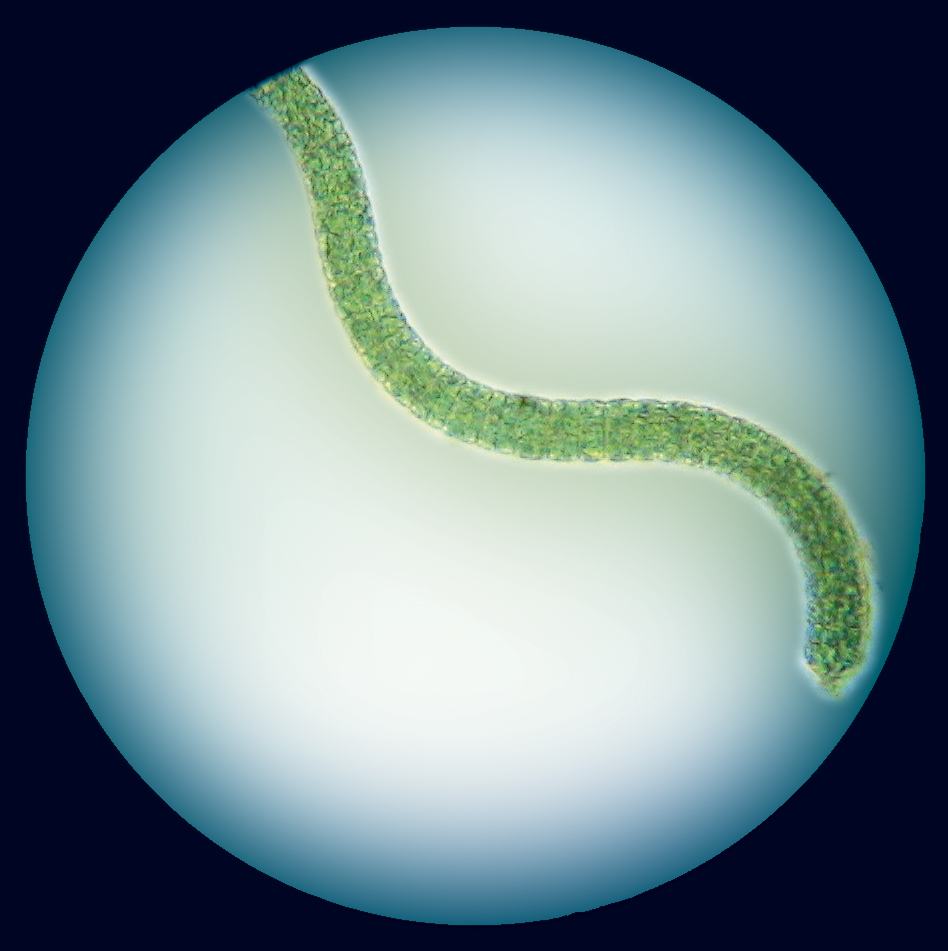

The cyanobacterium is better known as blue-green algae. It takes its name from a blue pigment, which, with chlorophyll, gives it a blue-green appearance. Its gelatinous clusters are recognizable when it is deposited on submerged parts of a rock or a pier.

It can reside in almost any terrestrial and aquatic habitat around the globe; fresh water, damp soil, rocks moistened temporarily in deserts, and even the bare ground. It is therefore quite normal to find it in Quebec lakes.

Normally, its presence is not an issue. However, in particular conditions, they can grow at great speed to ultimately cover almost the entire surface of a lake. The culprits? High concentrations of phosphorus, extreme temperatures, high intensity of UV rays, and the run-offs of certain agricultural herbicides.

We call these infestations harmful algal blooms (HAB). These blooms affect several elements of the aquatic ecosystem, including oxygen, temperature, and pH. At certain concentrations, they can be toxic to humans and wildlife; they then cause premature aging of aquatic environments.

A bloom of cyanobacteria may resemble blue-green scum or sometimes a large painted slick on the surface of the water. Being green like this is not so desirable!

Detection of cyanobacteria by air

One of the best ways to confirm the presence of cyanobacteria on a lake is still by direct sampling, but one must first be informed of its presence.

The most common detection method – by visual observation made by residents or municipal inspectors – is limited. The outbreak areas are not always visible or accessible on the water, and current methods make it difficult to find the problem’s point of origin.

Another monitoring technique is to use satellite imagery. It’s a rapid and accurate method, but its high cost and difficult data processing make it harder to use.

Recent technological advances introduced a new approach: low altitude assessment from the air.

Thanks to the miniaturization of sensors previously used on satellites, UAVs can now examine the surface of the water at low altitude. It’s now possible to inspect the surface of a lake in its entirety, at low cost.

In addition to generating data of higher resolution, imagers on UAVs are able to capture different wavelengths, revealing various structures on the water surface, such as blooms on a lake.

A study from the University of Kansas conducted in 2014 by Professor Deon van der Merwe has shown a correlation between the presence of cyanobacteria (confirmed in the analysis of samples) and the contents of aerial images taken using a UAV.

Link to the report summary (PowerPoint) HERE

Repeated analysis of images captured using UAVs allow, over time, the effective monitoring of the changes in bloom distribution. These analyses are also used to detect small algal accumulation zones along shorelines – a phenomenon that endangers wildlife and pets.

sUAS-based remote sensing methods provide valuable information that is complimentary to HAB risk assessment data derived from traditional methods, and could improve risk management at the local level. It is particularly useful in situations where the distribution pattern and surface density of a HAB needs to be characterized and tracked with a high level of spatial and temporal precision and accuracy.

– Deon Van der Merwe. PhD, Toxicology, Kansas State University, January 25 2016

You can read the full report here HERE

Fast, accurate, and economical, UAVs equipped with the right sensors can, in a few hours, produce a detailed picture of a body of water, revealing the development of cyanobacteria blooms and, possibly, the source of the problems.

Sources: CBC, MDDELCC, Atlas of Science, National Geographics, Kansas State University

Translated from French by Frédéric Jean